GUEST POST

The History of Schools in Britain: Part 1

Introduction

As dull as any self-respecting school student is liable to expect “The History of Schools in Britain” to be, I’m very happy to report that one only needs to dig a little under the humdrum surface of the average classroom to uncover a finely-tuned (if, at times, somewhat clumsily handled) system of education whose origins and intricacies stretch back almost two-thousand years.

This now-immense system of schools, which has grown slowly but inexorably across our nation’s storied and spectacular history, can be seen through one lens as a generation-spanning fellowship of miserable children shaving and sighing over spelling tests, long division, and Shakespeare; but through another as the quiet, relentless awakening of our nation’s individual and collective potential – an awakening which lies at the heart of why this small island nation became one of the most immensely powerful entities the world has ever seen, with its political ideas underpinning democracies across the globe and its convoluted hodge-podge of a language now the unquestionable “lingua franca” of all human civilisation.

In researching this topic, I have found a compelling answer to the question of why it is that Britain’s role in the world has been so historically disproportionate to its size, and I believe it is this: for the past two millennia, Britain’s culture has had a profound, underlying emphasis on and understanding of the importance of education in realising both individual and collective potential, and generations have made it their duty to promote this far and wide.

Now, this isn’t to say that education is the sole reason for Britain’s success: geography, natural resources, luck, tenacity, an individualist political culture, and the boldness and ingenuity of countless individuals across our history have all played their part, but the greater level of average education across our nation gave us a perennial edge, positioning us to take full advantage of the opportunities which came our way.

To us today, this seems like a bit of self-evident arithmetic: the greater the proportion of a nation’s children going to school and receiving a full education, the greater the share of that nation’s potential which is then unlocked and unleashed, to the benefit of all and sundry. To generations past, though, and even to many in the modern world, the idea that mass education is a worthwhile investment is not an obvious one, when culture does not advocate it and other concerns of survival seem more pressing. It is fortunate, then, that Britain can trace such a long history of valuing and promoting education, the first part of which we shall trace here:

In the Roman era, we see this through the adoption of Rome’s tiers of schooling and private tutoring, thus entrenching in Britain’s culture the everlasting principle that education in numeracy, literacy, philosophy, and theology is valuable as both a marker and component of success in life.

In the Middle Ages and through the Renaissance, this emphasis on education’s importance began slowly to spread from the nobility and clergy to the gentry and merchant classes, with clergymen like Augustine of Canterbury and Kings like Alfred the Great, Henry VI, and Edward VI promoting education across their realms and founding schools and universities; while countless merchants, clergymen, and nobles opened schools and left endowments to support education across Britain. That same emphasis on personalised learning continues today through options like online tuition.

In Part Two, we shall look at how, in the 18th-19th Centuries, the combination of industrialisation, urbanisation, and influential Enlightenment thinkers’ advocacy of education saw both the government and private sectors invest more time and resources than ever before in ensuring everyone in Britain had at least some access to education, establishing, both legally and philosophically, that every child needs and deserves a proper education; the mentality which still makes every child’s life miserable (for their own good) to this day.

What the Romans did for Us

It began, as so much of European History does, with the Roman Empire: after Emperor Claudius (41-54AD) invaded and thereafter “civilised” Celtic Britain in 43AD, Rome brought with it myriad technologies and innovations, stabilising and unifying the fractious kingdoms of Britannia with a “carrot-and-stick” of security and administrative and technological innovations, backed by the ever-present threat of brutal and efficient military repression.

Aside from the roads, arenas, and aqueducts, among the less-appreciated of these innovations were the schools – the ludi and grammatici – in which the children of Roman colonists, and those Britons who recognised the benefits of cosying up to them and learning to integrate with the Roman system, were taught essential skills of Latin, numeracy, administration, rhetoric, and the Rome-approved philosophies and traditions of the Romano-British corner of their vast territory.

Much like families seeking a private History tutor today, Roman noble families invested heavily in specialist education. Across the Empire, these schools were usually relatively informal institutions, centred around a single teacher: a relatively inexpensive “ludus,” run by a ludus litterarius, offered basic education to pupils up to the age of around 12; a somewhat more expensive grammaticus taught Greek, poetry, and more refined writing and speaking skills up to around 15; and a rhetor rounded off the education of those few elite boys whose families sought for them a career in law or politics.

While these schools catered primarily to the Middle and Upper classes of society, and undoubtedly served as a vital means of entrenching Roman culture, politics, and identity into those responsible for maintaining its imperial provinces day-to-day, they also laid the foundation of the systems which have steadily evolved into the very ones which torment us with exams to this day, along with the all-important cultural association of education with prosperity.

After the Romans “left” Britain — or, more accurately, the Roman Army withdrew from Britain to defend more important territories in 410AD, Britain’s connection to the centralised imperial state quickly crumbled, and the Roman state itself not too long after. However, four centuries of Roman rule had left their mark, and their institutions — all anyone had known for generations — did not disappear; they simply turned inward and shrunk in scale.

As post-Roman Britain fragmented once more into smaller, squabbling states, and the various invasions-cum-migrations of Germanic Jutes, Saxons, and Angles put further cultural, religious, and political pressure on these new institutions, administrative territories shrank in size and wealth, and responsibility for the tuition of the wealthier youth shifted steadily back to private tutors in the nobility’s courts and the remaining clergymen of the early Christian Church.

Going Medieval

This shift towards a combination of primarily church education and private tutors — themselves often religiously educated — continued throughout the Middle Ages, and it was religious institutions which set up the first recognisable schools in post-Roman Britain: in 595AD, Augustine of Canterbury, a Roman prior, was sent by Pope Gregory I on the ambitious mission of Christianising the Anglo-Saxon pagans, and a key aspect of this rather successful endeavour was the founding of a school, as part of the church which became St Augustine’s Abbey in Canterbury. Initially focused on teaching religious texts, this institution endures to this day as The King’s School, Canterbury, the oldest continuous school in the entire world.

While hundreds of small, church-adjoined schools were steadily founded over the following centuries, joining the clergy remained more or less the only way by which anyone whose family lacked the resources for tuition could obtain any more than the most rudimentary of educations. 9th Century Viking raids on monasteries further complicated education provisions: King Alfred the Great (871-899AD) lamented in writing the damage Viking raids had done to education and literacy in England, sacking monasteries and burning texts.

In response, along with his successful campaigns against the invading Danes, Alfred established a court school in Wessex to educate not only his own and his nobles’ children, but also promising students of lower birth, in both English and Latin.

Parish priests would often do what they could to educate the local youth in basic numeracy, literacy, and Christian theology, but without centralised programmes or funding, time and resources remained limited; thus, during the Middle Ages, most people would have possessed only a basic level of vernacular literacy and numeracy.

Nonetheless, Alfred’s advocacy of education took root, both in the courts and culture of England, and education remained a valued commodity as schools and colleges steadily sprang up across the centuries. For all his flaws, the pious Henry VI (1422-61, 1470-71), for example, endeavoured to invigorate education further, founding Eton College, King’s College Cambridge, and All Souls, Oxford.

As an aside, “literacy rates” in History can often be a little misleading: you may well have heard something like, “in the Middle Ages, only 10% of people were literate,” but it’s worth keeping in mind that “literate” in these times usually referred to someone who could specifically read and write Latin (the language of the Bible, Church, and communication across Christendom), while most people would nonetheless have been able to read and write to at least a functional extent (signs, bills, names, common words) in their local vernacular – just with highly inconsistent spelling.

Renaissance Men (and some women)

While the first independent grammar schools (that is, not part of a specific church) emerged in the 12th Century, it’s during the 14th and 15th Centuries that we see an explosion of both church-run and independent grammar schools across England, often funded by generous endowments from local nobles, merchants, and clergy, supplying educated men for the growing administrative, mercantile, and legal sectors.

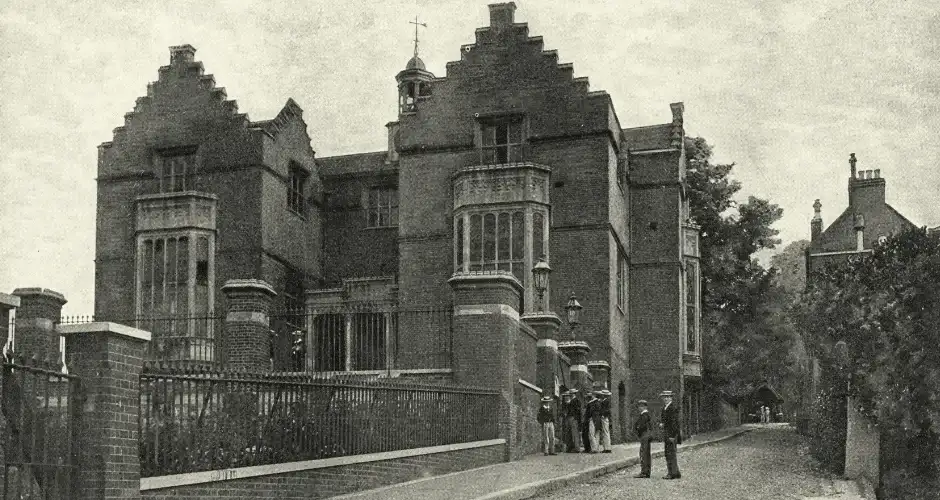

My own alma mater, Loughborough Grammar School, was among these, founded in 1495 in an upstairs room of the parish church (we’ve since moved) through a grant by local wool merchant Thomas Burton. While monarchs like Henry VIII (1509-47) and Edward VI (1547-53) deserve credit, this decentralised, philanthropic support for education was quite unique to Britain in this period, played a key role in our economic, political, and philosophical development.

The biggest factor in this growth was the Protestant Reformation, particularly after Henry VIII (1509-47) decided to circumvent Pope Clement VII’s refusal to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon (whose nephew, Charles V, was currently holding said Pope hostage) by breaking with Rome entirely. Highly educated himself, Henry’s reign saw far more schools founded than in previous centuries, marking the shift from primarily church-based to secular secondary education, while meeting a growing demand from a population who increasingly sought education for status and advancement.

It was Henry’s son, Edward VI, who truly reformed both theology and education, transitioning England from Henry’s rebranded Catholicism to verifiable Protestantism: through the printing press and the Bible now being legally available in English, English literacy grew, and the dissolution of the monasteries opened a market for educating the growing Middle Class.

Edward established the system of free, independent grammar schools – originally for boys, with girls tending to receive private tuition to whichever level their parents desired or could afford – in part to train a new cohort of Protestant clergy, and these became the backbone of Britain’s secondary education system until the 19th Century.

For younger children, smaller church schools and “Dame Schools,” often run by widows, would provide basic literacy and numeracy, and, from 1562, the seven-year apprenticeships mandated for all tradesmen provided many with a further degree of education.

Conclusion:

Through this brief overview, we’ve seen how, despite the turmoil of the First-through-Sixteenth Centuries in Britain, this consensus that education is always a worthwhile investment developed and endured, at times held back in practise by instability, lack of resources, and the shifting focuses of governments, but never forgotten or abjured.

Vitally, education was not seen as something simply to be hoarded for the elite, but rather as an asset which, while undoubtedly more accessible to the elite, and perhaps more immediately useful to them, so many across time invested their time and fortunes in promoting for all as both a moral and civic duty. As education has evolved, families now have more choice - from local schools to platforms where you can find a GCSE tutor online in a few clicks!

In Part Two, we’ll examine how Enlightenment ideas, religious and political strife, and the growing wealth and urbanisation of Britain through its Empire and the Industrial Revolution contributed to the development of our education system, both philosophically and practically.

References:

- Gillard D (2018) Education in the UK: a history

- The University of Reading. "A Long Way from Home: Diaspora Communities in Roman Britain - University of Reading". www.reading.ac.uk. Retrieved 9 October 2017

- Müller, Miriam (2018). Childhood, Orphans and Underage Heirs in Medieval Rural England: Growing Up in the Village

- David Mitch, "Schooling for all via financing by some: perspectives from early modern and Victorian England." Paedagogica Historica 52.4 (2016): 325-

- H. C. Barnard, A History of English Education from 1760, (1961), 2–4

- J.H. Higginson, "Dame schools." British Journal of Educational Studies 22.2 (1974): 166-181

- John William Adamson, English Education, 1789–1902, (1930), 114–127

Parents

Students

Tutors

James H

Tutor

Experienced Russell Group Tutor for English, History, Humanities, UCAS, and EFL/IELTS at all ages

Looking for a tutor?

Sherpa has hundreds of qualified and experienced UK tutors who are ready to help you achieve your goals. Search through our tutors and arrange a free 20 minute introduction through our industry-leading online classroom.

Find a TutorSimilar Articles